The scent of fresh bread and seaweed soup filled the little cottage as morning light poured through the open windows.

Mira sat at the table, her braid still damp from her morning wash, quietly spooning porridge into her bowl.

Garron was already halfway through his second helping, elbow on the table, chewing with the slow contentment of a man who had no intention of rushing the morning.

Elia wiped her hands on her apron and set down a small plate of pickled radish between them. “So,” she said casually, sliding into her seat, “the prince still hasn’t come back to visit?”

Mira paused mid-stir. “No,” she said simply.

Garron grunted. “Still in town, though. Saw him near the blacksmith yesterday. Hammering something.”

Elia raised a brow. “The prince?”

“With his own hands,” Garron said, stabbing a piece of radish. “Didn’t do too bad, either. Old Joe says he’s been helping fix the docks in the mornings.”

Mira kept her eyes on her bowl. “Sounds like he’s fitting in just fine.”

Elia tilted her head. “You sound almost disappointed.”

“I’m not,” Mira said quickly.

A beat passed.

Elia smiled slightly and leaned forward. “You know, if you were—”

“I’m not,” Mira insisted.

Garron chuckled. “He hasn’t come back, but he hasn’t left either. That’s saying something.”

“He’s probably just… resting,” Mira muttered. “Or hiding.”

“From what?” Elia asked, teasing.

Mira sighed. “From whatever royal business chased him out here in the first place.”

Her mother poured some tea. “Could be. But if you ask me, he’s not in any hurry to return to it.”

Garron leaned back in his chair. “Strange, though. For someone who looked so out of place the first day, he’s gotten comfortable. Too comfortable.”

“You think he’s up to something?” Elia asked, her tone turning just a little more serious.

“I’m not sure,” Garron said slowly. “And I’m not interested in finding out either. That’s the mayor’s problem.”

The table fell quiet for a moment.

Outside, gulls called in the distance. The breeze stirred the curtains.

Mira picked at her bread, then said quietly, “But we can't ignore him either. Especially his safety. If anything happens to him while he's in this town...”

Her parents exchanged a glance but said nothing.

And the morning went on—quiet, simple, but not without weight.

Something lingered in the air. Like fog before a storm...

Meanwhile, at the dock—

Seagulls squawked overhead, and the air smelled of salt, fish, and sweat.

Lucien grunted as he hoisted a net full of flopping mackerel onto the wooden planks. The net landed with a wet slap.

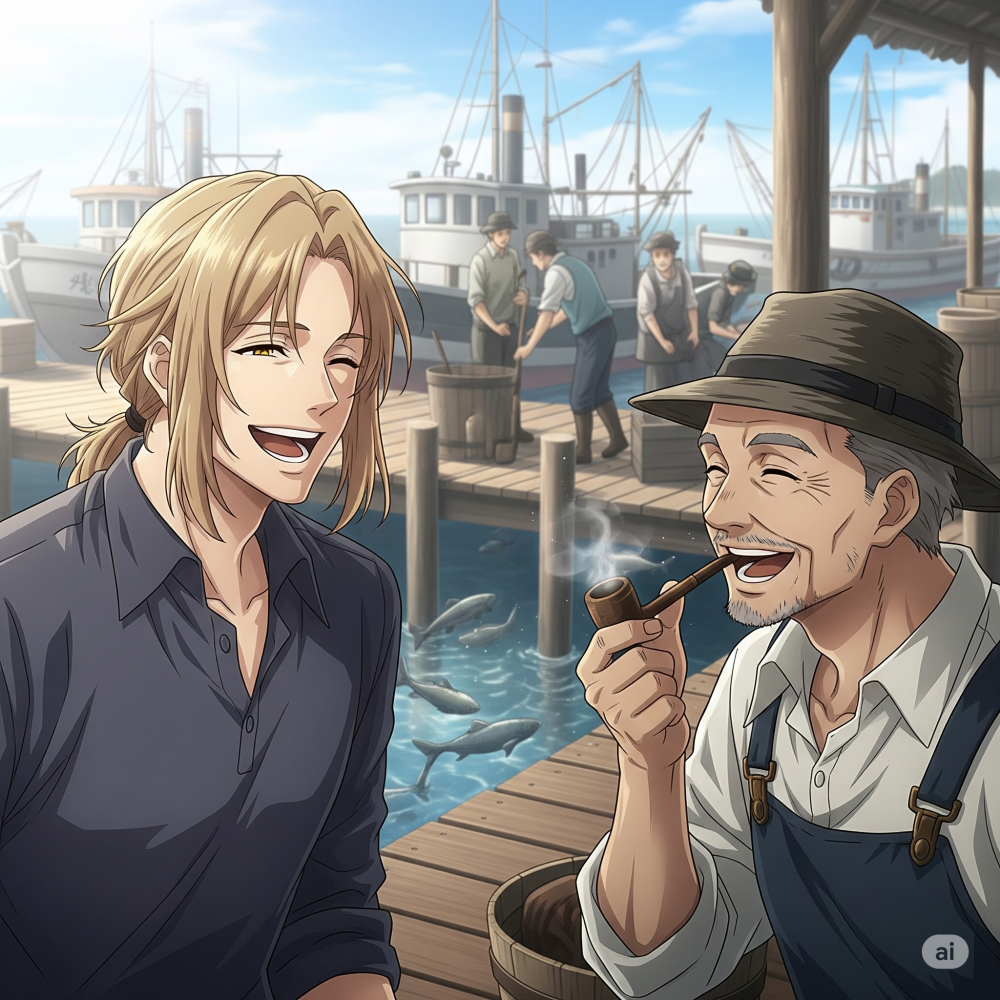

“That’s the fourth one, my prince,” Old Joe said, squinting at him from beneath his straw hat. “You planning to earn a knighthood or start a fish shop?”

Lucien wiped his brow with the sleeve of his borrowed tunic. “What can I say? The academy didn’t teach me how to gut fish, but I learn fast.”

“You learned backwards,” muttered a younger fisherman as he struggled with a tangled rope. “First day, you tried to unload a crate of eels upside down.”

“They were slippery,” Lucien said, deadpan. “And judgmental.”

Joe let out a wheezing laugh. “He’s got the spirit, at least.”

A boy no older than thirteen ran by with a basket of shellfish. “Mister Prince, sir! You coming to the cookout later?”

Lucien raised an eyebrow. “Cookout?”

“Yeah! Everyone’s bringing something. I’m bringing clams!” the boy declared proudly before dashing off down the dock.

Lucien looked back at Joe. “That's what I get for a day’s work?”

Joe shrugged. “That, and a sore back.”

16Please respect copyright.PENANAvHBVyQxJWz

16Please respect copyright.PENANAvHBVyQxJWz

A splash came from the side of the dock. Another net full of fish hit the water, narrowly missing Lucien’s boots.

He raised a brow. “That wasn’t me.”

“That one was on me,” grinned Thom, a burly man with sleeves rolled up to his shoulders. “Figured I’d keep you humble.”

Lucien stepped aside and pointed at his feet. “Next time, please don’t humble me with ten pounds of trout.”

“Fair,” Thom chuckled, then handed him a bucket. “Here. Deliver this to the inn. They’re cooking the catch.”

Lucien accepted the bucket and glanced at the fish inside. “Still flapping.”

“Means it’s fresh,” Joe said, smirking.

Lucien turned to go, then paused. For a second, he looked out at the sea—blue and open, stretching far beyond the cliffs.

He had come to this town out of curiosity—chasing rumors of the Saintess of the South.

But now?

Now he knew how to tie a fishing knot. He knew the names of half the dockworkers.

He knew Mira lived just uphill, in the cottage with the red roof and the big tree beside her workshop.

But she still hadn’t come to see him.

Not even once.

Lucien sighed and adjusted the bucket in his grip. “Do I smell like fish?”

Joe didn’t look up from cleaning the net. “You've got a bucket of fish on your back. What do you think?”

“Perfect,” Lucien muttered, and started toward the town square.

But he didn’t get far before a familiar shadow fell across the path.

Cassian stepped out from between two crates stacked near the market lane, his cloak caught lightly in the breeze—as if even the wind knew not to sneak up on him.

Lucien slowed. “If you're about to ask me to haul more fish, I’ll personally jump into the sea.”

Cassian didn’t smile. His eyes swept over Lucien once, then flicked to the bucket in his hand. “Still playing local?”

"I'm not playing, Cassian. I'm living. As a matter of fact, I’ve never felt so alive in my life before." Lucien grinned—widely.

Cassian fell into step beside him, silent for a few paces. Then: “We have a problem.”

Lucien glanced sideways. “Of course we do. What kind this time?”

Cassian kept his voice low. “People have been arriving. Travelers. Not merchants. Not fishermen. Strangers.”

Lucien's eyes narrowed. “Tourists?”

“Armed tourists, then. Light-footed. Watchful. Too well-dressed to be vagrants. Too quiet to be common,” Cassian said, his tone tight.

Lucien's hand tightened slightly on the bucket handle. “Spies?”

Cassian paused, then added, “Could be. Could also be scouts. Or worse—pilgrims with an agenda.”

Lucien exhaled slowly. “Could they'd come for me?”

Cassian shook his head. “I don't think so. I heard them asking questions about the Saintess of The South.”

Lucien frowned. “Temple?”

Cassian gave a slow nod. “Most likely. And it's just a matter of time before they find her. After all, everyone in this town know her."

They turned a corner, the cobbled street narrowing. Ahead, the roof of the inn peeked through the treetops.

Lucien lowered his voice. “Has anyone approached her?”

“No,” Cassian said. “They’re cautious. Watching. Waiting.”

Lucien stopped walking.

A few gulls called lazily overhead. Somewhere nearby, a child laughed.

But the weight in his chest was unmistakable.

“I came here to find her,” he murmured. “Not to bring trouble.”

Cassian looked at him, unreadable as ever. “Then maybe you should’ve left.”

Lucien gave a humorless chuckle. “It’s a bit late for that.”

Cassian didn’t argue.

Lucien finally handed him the fish bucket. “Here. Deliver this to the inn. I need to think.”

Cassian took it with a raised brow. “Am I your squire now?”

“Try not to eat the trout.” Lucien turned back toward the hill—toward the cottage with the red roof, and the girl who hadn’t come to see him.

The wind was picking up again.

So were the eyes watching in its wake.

16Please respect copyright.PENANA0GqftnxyrF